Abstract

Introduction: Closure of the hernia gap in laparoscopic ventral hernia repair before mesh reinforcement has gained increasing acceptance among surgeons despite creating a tension-based repair. Beneficial effects of this technique have been reported sporadically, but no evidence is available from randomised controlled trials. The primary purpose of this paper is to compare early post-operative activity-related pain in patients undergoing laparoscopic ventral hernia repair with closure of the gap with patients undergoing standard laparoscopic ventral hernia repair (non-closure of the gap). Secondary outcomes are patient-rated cosmesis and hernia-specific quality of life.

Methods: A randomised, controlled, double-blinded study is planned. Based on power calculation, we will include 40 patients in each arm. Patients undergoing elective laparoscopic umbilical, epigastric or umbilical trocar-site hernia repair at Hvidovre Hospital and Herlev Hospital, Denmark, are invited to participate.

Conclusion: The gap closure technique may induce more post-operative pain than the non-closure repair, but it may also be superior with regard to other important surgical outcomes. No studies have previously investigated closure of the gap in the setting of a randomised controlled trial.

Funding: The study is funded by The University of Copenhagen and private foundations.

Trial registration: NCT01962480 (clinicaltrials.gov).

Abstract

Introduction: Closure of the hernia gap in laparoscopic ventral hernia repair before mesh reinforcement has gained increasing acceptance among surgeons despite creating a tension-based repair. Beneficial effects of this technique have been reported sporadically, but no evidence is available from randomised controlled trials. The primary purpose of this paper is to compare early post-operative activity-related pain in patients undergoing laparoscopic ventral hernia repair with closure of the gap with patients undergoing standard laparoscopic ventral hernia repair (non-closure of the gap). Secondary outcomes are patient-rated cosmesis and hernia-specific quality of life.

Methods: A randomised, controlled, double-blinded study is planned. Based on power calculation, we will include 40 patients in each arm. Patients undergoing elective laparoscopic umbilical, epigastric or umbilical trocar-site hernia repair at Hvidovre Hospital and Herlev Hospital, Denmark, are invited to participate.

Conclusion: The gap closure technique may induce more post-operative pain than the non-closure repair, but it may also be superior with regard to other important surgical outcomes. No studies have previously investigated closure of the gap in the setting of a randomised controlled trial.

Funding: The study is funded by The University of Copenhagen and private foundations.

Trial registration: NCT01962480 (clinicaltrials.gov).

Laparoscopic umbilical or epigastric hernia repair is a common surgical procedure. Compared with open repair, laparoscopic repair may have potential advantages in terms of less wound infections and shortened hospital stay [1]. However, there are still clinical challenges after this procedure in terms of severe post-operative pain, wound-related problems, cosmetic complaints and high rates of 30-day readmission [2-10]. Standard laparoscopic umbilical or epigastric hernia repair is performed by fixating the mesh (intraperitoneal onlay mesh (IPOM)) without closing the hernia gap. This is done to create as little tension as possible. Despite the risk of creating increased tension to the tissue, closing the gap is gaining increasing acceptance among surgeons owing to a possible prevention of mesh protrusion through the gap (bulging), which provides a better cosmetic result, possibly lowers the recurrence rate and improves abdominal wall function [6, 11-13]. The technique may also decrease seroma formation [2] and improve overall patient satisfaction [6, 14]. These beneficial effects are, however, not supported by randomised controlled evidence, and the effects of gap closure on post-operative pain and recurrence have not been investigated.

However, closure of the gap may induce more intense post-operative pain compared with a non-closure technique. The primary purpose of the present study is therefore to compare early post-operative pain levels in patients undergoing closure of the gap and IPOM with pain levels in patients undergoing non-closure of the gap and IPOM in laparoscopic umbilical or epigastric hernia repair. Secondary outcomes are patient-rated cosmetic results, hernia-related quality of life (QoL), movement limitations, fatigue, general well-being, and 30-day-readmission and morbidity.

METHODS

Study design

This will be a randomised, controlled, double-blinded study which includes a total of 80 patients undergoing elective laparoscopic umbilical or epigastric hernia repair. Patients are randomised to an intracorporally sutured closure technique of the hernia gap and IPOM or to non-closure of the gap and IPOM (standard procedure). Patients are recruited from two university hospitals.

Surgical technique

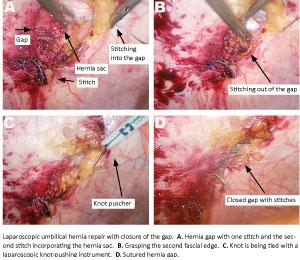

Intraperitoneal onlay mesh and closure of gap (intervention group)

The hernia gap is sutured with non-absorbable suture (Ethibond Excel 2-0, Ethicon, NJ, USA). The hernia sac is incorporated into the sutures. The stitches are placed at a distance of 0.5-1 cm from the fascial edges and with 0.5-1 cm between the stitches. Suturing is performed at 6-8 mmHg IPP.

We intend to incorporate all layers of the abdominal wall except the skin and subcutis in the stitch. Each stitch is tied with at least four knots.

Intraperitoneal onlay mesh and non-closure of gap (control group)

The standard surgical technique is without closure of the gap before IPOM fixation with the above described double-crown technique.

Both surgical groups

Four experienced laparoscopic hernia surgeons will perform the operations. Before study start, each surgeon has performed more than 30 intracorporally sutured repairs. The abdominal cavity is insufflated to 12 mmHg by Verres needle, and a 12-mm trocar is placed along the left side laterally to the mid-clavicular line under the lower left costa. Additionally, one 5-mm trocar and one 12-mm trocar are placed in a vertical line downward. This regimen is chosen in order to meet local choice of procedures. Adhesiolysis is performed as needed. The gap area is cleared for fatty tissue, and the falciform ligament is partially detached from the abdominal wall. The maximum diameter of the gap is measured under a 6-8 mmHg intraperitoneal pressure (IPP) before fixation of the mesh and/or suturing of the gap. A Physiomesh (Ethicon, NJ, USA) is placed with at least a 5-cm overlap (measured on the non-sutured gap) of the gap and fixated with double-crown technique (Protack; Covidien, CN, USA). The gap size before closure is used to determine the size of mesh. The hernia content is reduced, without removal of the hernia sac. The mesh fixation is performed under a 6-8-mmHg IPP with 1.5-2 cm distance between tacks. 10 ml bupivacaine 0.5% are administered into the trocar sites (4 ml in the two 12-mm trocar sites and 2 ml at the 5-mm trocar site) at the end of the hernia repair. Furthermore, a surgeon-administered transabdominal transverse abdominis plane (TAP) block is applied under visual guidance [15] after the mesh fixation before end of operation. Thirty ml of bupivacaine 0.5% is injected with an 18G needle at four points of the abdomen (right and left side of the abdomen in the mid-clavicular line on the insufflated abdomen, 3 cm caudally and 3 cm cranially to the umbilicus).

Fascial trocar site defects > 5 mm are closed with polydioxanone PDS interrupted sutures, and skin is closed with nylon 3-0, single stitches. A fitted abdominal binder is placed around the abdomen when the patient is mobilised from the operating table to the post-operative care unit (PACU) bed. The patients are instructed to wear the binder continuously for seven days (can be removed when showering).

Standard anaesthesia and analgesic treatment

At the induction of anaesthesia, 16 mg methylprednisolonsuccinat is administered intravenously (IV) and 1,500 mg cefuroxime IV are injected. Patients are anaesthetised using propofol 3-5 mg/kg/hour and remifentanil 1 microgram/kg/hour. If relaxation (rocuronium) is needed, this is registered by the surgeon in the registration form. At the end of the procedure, pain is controlled intraoperatively with sufentanil 0.15 microgram/kg IV and toradole 30 mg IV. Post-operative pain is controlled with morphine (0.1 mg/kg) administered until a 0-100 mm visual analogue scale (VAS) < 20 is reached. Post-operative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is treated with ondansetrone 4 mg IV. One litre of isotonic saline is infused during the surgical procedure independently of the patient’s weight.

The post-operative analgesic regimen after discharge from the post-anaesthesia care unit is with paracetamol 1,000 mg, four times daily and ibuprofen 400 mg four times daily.

Patients are carefully instructed to take the tablets four times daily for the first five days in their private homes. All post-operative analgesic treatment is provided by project personnel at discharge.

Inclusion criteria

– Elective repair (primary or recurrent, except for previous IPOM technique, see exclusion criteria below).

– Laparoscopic umbilical or epigastric hernia repair.

– Umbilical trocar-site hernia and epigastric trocar-site hernia within 8 cm caudally to the processus xiphoideus.

– Defect gap 2-6 cm estimated preoperatively.

– Not more than one defect.

– Patients aged 18-80 years.

Exclusion criteria <

– Open hernia repair.

– Previous IPOM technique.

– Defects less than 2 cm or more than 6 cm (measured preoperatively or intraoperatively).

– Poor compliance (language problems, dementia and drug or alcohol abuse (more than 60 g alcohol/day)).

– Emergency repair.

– Chronic pain syndrome (chronic back pain, chronic headache, severe dysmenorrhoea, fibromyalgia, whiplash or other conditions requiring daily pain medication).

– Daily consumption of opioids (three weeks before surgery).

– Decompensated liver cirrhosis (Child-Pugh B-C).

– If a patient withdraws his/her inclusion consent.

– Epidural or spinal block administered.

Outcomes and measurements

Before the operation, patients are carefully instructed to use the VAS and a verbal rating scale (VRS) and to register at 6:00 pm every post-operative test-day.

Primary outcome

Pain during activity (mobilisation from supine to sitting) on the first post-operative day (at 6:00 pm), approximately 24 hours after the hernia repair. For this purpose, patients register using a VAS questionnaire (0 = no pain, 100 = worst imaginable pain) supplemented with registrations on a VRS regarding pain levels during activity (no pain, little pain, moderate pain, severe pain during mobilisation from lying to sitting position).

Secondary outcomes

– VAS pain and VRS pain are recorded preoperatively and at days 2, 3, 7, and 30.

– Movement limitations (0 = no movement limitation, 100 = maximum movement limitations), fatigue (0 = no fatigue, 100 = maximum fatigue) and general well-being (0 = no decreased general well-being, 100 = maximally decreased general well-being) are re-corded preoperatively and at days 1, 2, 3, 7 and 30.

– Degree of nausea and number of vomiting episodes are recorded the first 24 hours after surgery.

– Cosmesis satisfaction are measured at day 30 post-operatively using a numeric rating scale supplemented with two verbal rating scales as described in previous studies [16].

– Hernia-specific quality of life (QoL) is measured using the Carolina Comfort Scale (CCS) [17] at post-operative day 30.

– Morbidity (30-day follow-up by clinical visit, Green System, etc. (inclusive visits at the family doctor).

30-day readmission rate (follow-up by clinical visit, Green System, etc.)

Sample size calculation

A previous study from our group found that VAS pain during activity the first post-operative day after laparoscopic umbilical or epigastric hernia repair with tack fixation was (mean) 57 mm with a standard deviation (SD) of 26 mm. Patients received an analgesic post-operative regimen almost identical to that of the present study (patients in the present study will have additional surgeon-administered TAP block, which was not performed in the former procedures).

We considered a 30% increase in pain levels (that is a VAS increase of 17 mm (= MIREDIF) from VAS = 57 to 74 mm) to be clinically relevant. With 80% power and a 0.05 significance level (alpha 2-sided), the number of patients needed to demonstrate a difference in pain levels between the intervetion and the standard technique is 38 patients in each randomisation arm. To account for the analgesic effects on the primary outcome using surgeon-administered TAP block, we chose to increase the inclusion number to 40 patients in each arm. We have briefly discussed an alternative sample size calculation based on a non-inferiority design in the Discussion section.

Statistical analysis plan

The data will be handled according to the principle of intention-to-treat (ITT). Thus, patients stay in the originally assigned groups. For continuous variables, we use the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test to compare the surgical groups. A χ2-test is used to compare dichotomous variables. The non-parametric analysis of variance (Friedman’s test) is used to investigate the effect over time of pain, movement limitation, fatigue and general well-being during the study period within and between study groups [18]. In addition, the area under the curves comparing summed VAS scores is analysed using a Mann-Whitney test. If continuous data are parametric, we use Student’s t-tests to compare means between groups and two-way ANOVA tests to investigate the effect over time of pain. When appropriate, 95% confidence intervals are used. p < 0.05 is considered significant.

Blinding and randomisation

Randomisation (in blocks of four) is performed centrally using a computer generated randomisation list. An excluded patient is replaced by a block of four. A non-transparent envelope is made for each patient. The envelope contains the code for closure of the gap or no closure of the gap.

Randomisation is performed after the surgeon has prepared the defect area for mesh fixation.

Ethics and trial registration

The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (ID no.: 2007-58-0015), the ethics committee (ID no. H-3-2013-164), and was registered with clinicaltrials.gov (ID no.: NCT01962480). The study is funded partly by The University of Copenhagen and partly by private funds.

DISCUSSION

Many patients will experience severe early post-operative pain after laparoscopic ventral hernia repair [4, 5], the aetiology of which is multifactorial [19]. Tension-free repair has been the surgical gold standard for decades. Closure of the hernia gap may increase the risk of post-operative pain due to increased tension on the abdominal wall. On the other hand, closure of the gap may provide advantages, such as better abdominal wall function, a better cosmetic result, reduced recurrence rates and a lower risk of seroma formation [2, 10, 11], but findings are not uniform [2, 11, 13, 14]. However, the present planned study may be regarded as exploratory since differences in pain levels between the two techniques have not previously been investigated. Accordingly, a non-inferiority design with equal pain intensity in both study groups (sample size calculation with a non-inferiority margin of 15 mm) would call for 38 patients in each randomisation arm). From our conventional sample size calculation (see above), we chose to include 2 × 40 patients in the present study. In this study, we chose to use surgeon-administered TAP block and not TAP block guided by ultrasound. The literature has found beneficial effects of TAP block for laparoscopic surgical procedures using ultrasonographic guidance. The efficacy of surgeon-administered TAP block without ultrasonographic guidance has been sparsely investigated in six small, retrospective case-control studies or case reports in patients undergoing Caesarean section, liposuction, breast surgery with abdominal flap reconstruction, or open hemicolectomy. These studies found that surgeon-administered TAP block had a significant pain-reducing effect during the first 24 post-operative hours [15].

The present study is the first randomised, controlled, double-blinded study comparing closure of the hernia gap with non-closure of the gap. Our primary objective is early pain intensity. Secondarily, we test the effect of closing the gap on the cosmetic result, hernia-specific QoL, movement limitations, fatigue, general well-being, 30-days readmission and 30-day complications.

Correspondence: Mette W. Christoffersen, Kirurgisk Sektion, Gastroenheden, Hvidovre Hospital, Kettegård Allé 30, 2650 Hvidovre, Denmark. E-mail: mette.willaume@gmail.com

Accepted: 11 April 2014.

Conflicts of interest: Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at www.danmedj.dk.

REFERENCES

Sauerland S, Walgenbach M, Habermalz B et al. Laparoscopic versus open surgical techniques for ventral or incisional hernia repair. Cochrane database 2011;(3):CD007781.

Chelala E, Thoma M, Tatete B et al. The suturing concept for laparoscopic mesh fixation in ventral and incisional hernia repair: Mid-term analysis of 400 cases. Surg Endosc 2007;21:391-5.

Morales-Conde S. Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair: advances and limitations. Semin Laparosc Surg 2004;11:191-200.

Bisgaard T, Kehlet H, Bay-Nielsen M et al. A nationwide study on readmission, morbidity, and mortality after umbilical and epigastric hernia repair. Hernia 2011;15:541-6.

Eriksen JR, Poornoroozy P, Jorgensen LN et al. Pain, quality of life and recovery after laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. Hernia 2009;13:13-21.

Clapp ML, Hicks SC, Awad SS et al. Trans-cutaneous closure of central defects (TCCD) in laparoscopic ventral hernia repairs (LVHR). World J Surg 2013;37:42-51.

Agarwal BB, Agarwal S, Gupta MK et al. Laparoscopic ventral hernia meshplasty with “double-breasted” fascial closure of hernial defect: a new technique. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech Part A 2008;18:222-9.

Cobb WS, Kercher KW, Heniford BT. Laparoscopic repair of incisional hernias. Surg Clin North Am 2005;85:91-103.

Liang MK, Berger RL, Li LT et al. Outcomes of laparoscopic vs open repair of primary ventral hernias. JAMA Surg 2013;148:1043-8.

Palanivelu C, Jani KV, Senthilnathan P et al. Laparoscopic sutured closure with mesh reinforcement of incisional hernias. Hernia 2007;11:223-8.

Palanivelu C, Rangarajan M, Parthasarathi R et al. Laparoscopic repair of suprapubic incisional hernias: suturing and intraperitoneal composite mesh onlay. A retrospective study. Hernia 2008;12:251-6.

Agarwal BB, Agarwal S, Mahajan KC. Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair: innovative anatomical closure, mesh insertion without 10-mm transmyofascial port, and atraumatic mesh fixation: a preliminary experience of a new technique. Surg Endosc 2009;23:900-5.

Franklin ME, Jr., Gonzalez JJ, Jr., Glass JL et al. Laparoscopic ventral and incisional hernia repair: an 11-year experience. Hernia 2004;8:23-7.

Zeichen MS, Lujan HJ, Mata WN et al. Closure versus non-closure of hernia defect during laparoscopic ventral hernia repair with mesh. Hernia 2013;17:589-96.

Brady RR, Ventham NT, Roberts DM et al. Open transversus abdominis plane block and analgesic requirements in patients following right hemicolectomy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2012;94:327-30.

Bisgaard T, Klarskov B, Trap R et al. Microlaparoscopic vs. conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective randomized double-blind trial. Surg Endosc 2002;16:458-64.

Heniford BT, Walters AL, Lincourt AE et al. Comparison of generic versus specific quality-of-life scales for mesh hernia repairs. J Am Coll Surg 2008;206:638-44.

Tolver MA, Strandfelt P, Bryld EB et al. Randomized clinical trial of dexamethasone versus placebo in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg 2012;99:1374-80.

Wassenaar E, Schoenmaeckers E, Raymakers J et al. Mesh-fixation method and pain and quality of life after laparoscopic ventral or incisional hernia repair: a randomized trial of three fixation techniques. Surg Endosc 2010;24:1296-302.